Tradition in the Here and Now!

vol.3

Tatami and Living Thoughtfully

Maeda Toshiyasu President, Maeda Tatami Company

2019.05

Lifestyles have changed in Japan in recent years and domestic demand for the rush (igusa) matting used for tatami mats, which were the main flooring in Japanese homes through the twentieth century, dropped from 45 million mats in 1993 to 16.7 million mats in 2013, a space of only 20 years. While the situation might seem dire to some of the many tatami shops in Japan, Maeda Toshiyasu thinks it may be the perfect opportunity to not only raise awareness about the appeal of tatami but think about what he calls "living thoughtfully" (teinei ni kurasu) based on the merits of tatami. In 2012, to help people in disaster-stricken areas, he launched the "5 days 5000 Tatami Promise" Project together with other tatami makers throughout the country.

I inherited our family-run tatami manufacturing company, but that was in 1995, after I had graduated from university and worked in a bank for three years. I had not intended to follow in the family footsteps. I took a job in a bank right after graduating. I boasted to my father that I would one of those who lend money, not borrow it, as had so often been his fate as a tatami maker. Yet actually I myself liked the making things, and I gradually wanted to preserve the business that had been passed down in our family. My university seniors and friends thought I was weird for wanting to be a "mere tatami-maker," but their snide comments just added fuel to my determination to be one. Anyway, I decided to give it a try.

An Overly Optimistic Start

Before I quit the bank to go into the tatami business, my father had warned me many times: "It's not easy running a business." So I thought that I had prepared myself sufficiently, but I now realize that I didn't have the slighted idea what he meant. I was so optimistic. I got my former bank associates and other friends to introduce me to clients and was ready to go, but I didn't get any orders!

Finally, about half a year after I started, I got a job for the mats for a four-and-a-half-mat room. But when I went to collect my fee a month after finishing the job, the company had disappeared! Psychologically, that was a low blow. But somehow that experience flicked a switch in my brain. I realized there was much more I could do to drum up work. Instead of just waiting for jobs through construction contractors, I started introducing myself when a new house was being built or at local inns and lodging houses. I would bring along all sorts of samples and make suggestions. If they said they wanted me to "come right away," I'd drop everything and go, and I'd go pick up tatami whenever the customer wanted--day or night or weekends. If people dropped by the shop to ask about tatami, I could talk for an hour . . . And gradually word got around that there was this "guy crazy about tatami" in town, and people began to introduce me to their friends. I think it is thanks to the mistakes I made at the beginning that I was able to find the kind of business that suits me and build it up to what I have today.

©Nakasai Chiya

Tatami edging tape is available in all sorts of designs and colors.

©Nakasai Chiya

Inheriting the Old and Exploring the New

Of course I learned all the aspects of the work my father was doing, but I also wanted to find work that only I could do. My father would accept any work, no matter how difficult, and while I carried on that tradition, I thought it might be good to cultivate closer relations with customers. I would make regular rounds of potential customers and in the process, find out what they wanted, and in fact that effort did bring us increased work.

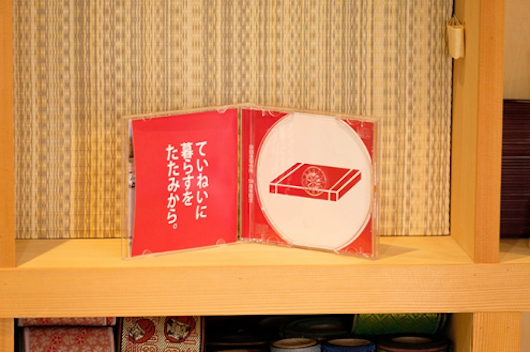

My father had developed a special tatami for judo floors, and I thought we should make it our own trademark product, so I asked Olympic gold medalist Koga Toshihiko--who is known as the Sanshiro of Heisei --to critique it. We kept improving it based on his feedback and perfected what we now call "Judo tatami: Sanshiro." [The caption says "Sanshiro Tatami"] In 2008 it received the official approval of the All Japan Judo Federation, and that recognition allows it to be used for national tournaments.

Most of the other officially approved judo mats are made by sports goods manufacturers, but since we are tatami craftsmen, we wanted it to have qualities distinctive to our craft. We focused special attention on the tatami surface. The surface of judo floor tatami is made with leather, but we wanted to get it as close as possible to the original quality of woven rush tatami. The tatami mats used in ordinary homes "breathe," so they absorb moisture and then diffuse it. That's why it is not sticky and damp in summer and why it is warm and insulating in winter. We negotiated with a major leather manufacturer and got them to develop a product with these qualities of natural tatami in the leather needed for judo mats.

Then, to get not just the upper surface right but the nonslip undersurface to suit our own image, I traveled all over looking for the right material. Ultimately, I found what we needed right in our own city of Kobe. Kobe is famous for its shoe-making industry, and I discovered that I could find both the technology and the materials I needed for the judo tatami right here. It surprised me. Before that I'd had known nothing about what was right there in my own city.

©Nakasai Chiya

"Sanshiro" tatami is made up of six to eight layers. It has greater cushion than household tatami to absorb the shock of judo throws.

The "Living Thoughtfully" Idea

The concept we developed at Maeda Tatami is "'Teinei ni kurasu' o tatami kara" (lit., living thoughtfully, from the tatami up). By "thoughtfully" (teinei ni), we mean doing things carefully and conscientiously. It involves being considerate of the people around you and putting into practice what you think they want to do by putting yourself in their shoes. Living that way, I sometimes look like someone going against the current of the times. As an example, it used to be common that the making of mochi rice cakes together in preparation for the New Year was a local community event. It was a chance for people who are too busy to meet much during the year to work together and nurtured a sense of community. But recently few such events are held. So I started to take the lead in holding a mochi-making gathering in my neighborhood. I think we should keep up such good traditions.

In my day-to-day work as well, I try to think carefully about how our customers will use their tatami-floored rooms and for what specific purpose. Is the room south facing or north facing? Is it a room for small children? A room where lots of people gather. The type of tatami that is most appropriate differs from one purpose to another. I think this kind of care and attention is important in daily life. This kind of expertise is important, but no matter how specialized the skills we offer, thoughtfulness is vital.

©Nakasai Chiya

Raising the Awareness of Children

I hold tatami workshops designed for children--I've been doing this for fifteen or sixteen years now. I have the participants each make a small tatami, about A4 size. Watching them closely in the process of making the mats and enjoying the sense of achievement together with them is delightful, no matter how many times I do it.

But we don't just make tatami. I explain to the children about the kind of people who are involved in the process of making tatami. We live in a time when you can obtain whatever you want with the touch of a finger, so people come to take the things around them for granted and have no idea where they came from. So, using tatami, which is familiar to children, I explain about all the things that go into making tatami: the structure of the tatami mats, the rush grass from which the covering mats are woven, the farmers who grow the rush grass--there's a lot to talk about--maybe it takes longer than actually making the tatami!

Once they've attended the workshop, children know exactly how the tatami is made that they sat on without even thinking before. I hope that experience will encourage them to think about the other things around them--wonder how they are made and by what kind of people.

This is the idea behind "living thoughfully." If children think about the farmers' labors in growing rice and the truck drivers' work of hauling it long distances to market, they will not have to be told "Finish your rice; don't waste even a grain" and they will naturally eat everything they are served.

I even made an original kamishibai (paper play) story to explain the tatami-making process. At first I was a bit embarrassed trying to be a storyteller, but the children get quite absorbed and even their mothers sitting behind them look very pleased, nodding once in a while. Of course, it's still a bit embarrassing and I'm no pro storyteller, but it's meaningful that a tatami maker does something like this.

©Nakasai Chiya

A4 size tatami made in the workshop. The participants can choose their own border tape.

©Nakasai Chiya

Original kamishibai. The story is by Mr. Maeda.

Sending New Tatami after Disaster

In 2012, I launched a project to provide new tatami to evacuation centers in case of a major disaster. It all began after the Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami Disaster of March 2011. Seeing the evacuees on the cold gymnasium floors of the schools that were the evacuation centers, I immediately thought if only I could send them tatami it might soften at least some of the pain they were experiencing. But I knew there would be a limit to what I could do as one individual. Even if I carried tatami to the evacuation centers, it might be more trouble than help, and who would I contact if I wanted to do such a thing? Thinking about all these things, I ultimately was not able to help the 2011 disaster victims at all.

So what should I do in order to be able to help? I consulted all sorts of people, including people at my local government office. Then I talked to people who had stayed in evacuation centers after the 2011 disaster. One mother told me "The center where we were just had thin blue vinyl sheets on the floor. If it had been tatami, I could have nursed my 11-month-old baby while sleeping on the floor." When I heard stories like that, I knew I had to figure out a way to do something.

Providing tatami had to be a help that would not conversely be a hindrance and I couldn't do it by myself. I had to create a network of people who would be able to go into action as soon as a disaster occurred. Thinking it would be a good idea to draw up disaster-assistance agreements with the local governments who operate evacuation centers, I visited city halls and local government offices, but the results were not satisfactory. The main problem was that, with the few other tatami shops that were willing to collaborate with me at that time, we could only provide about 50 tatami on short notice after a disaster, and that would not be nearly enough to cover the need.

Other Tatami Makers Had the Same Idea

Whenever I would talk about my idea with other tatami makers, they all said, "I had the same idea," and were eager to collaborate. The number of tatami makers who joined the project gradually increased, and today, the participants in the project number about 500 tatami makers from Hokkaido to Kyushu. They help not only when disasters occur but collaborate for disaster prevention drills. And with our activities going on over the years, we now have disaster-assistance agreements with about 160 local governments.

This is the "5 days 5,000 Tatami Promise," and this is how it works. Member tatami shops declare how many tatami mats they can provide in case of disaster--whether it is 10 mats or even 1 mat. And they can change that figure from one year to the next. Each shop has to bear the cost of shipping the tatami to the evacuation centers, so they figure the number of tatami they offer to provide within their means. When a disaster occurs, Project tatami shop members who are safe and able to get around go to the evacuation centers in their area and find out what the situation is. They report to the local government and community members how many mats are needed, being careful to assure that the mats when delivered will not occupy valuable space needed for other goods or get in the way. That process takes place on Day 1. On Day 2, Project members in other parts of the country begin to make the mats, finishing on Day 3. The mats are shipped on Day 4 and from Day 5, the disaster zone Project members receive the mats and transport them to the evacuation center. Japan has a total of 47 prefectural units and we began with a target of 100 mats per prefecture--that is where we got the "5,000" figure.

I was the person who first came up with the idea for the Project, but all the members are local tatami makers who want to make a difference in a disaster and put their skills to use in protecting their local area. Everyone plays a part, and that is the "Promise" part of the project. We "promise" to help, and that is a greater responsibility than any "duty" or assignment.

The Project mobilized first in 2014 at the time of the major earthquake in northern Nagano prefecture. We sent 40 tatami. In 2015, we mobilized twice. Then, at the time of the April 2016 earthquake in Kumamoto, we provided 6,000 mats to 40 evacuation centers. At that time, 200-300 shops not only in Kyushu but in various parts of Japan sent freshly made tatami to Kumamoto in one relay after another. And after the tatami were delivered, local tatami shop owners made the rounds of the centers to give advice on sanitary use of the mats. The standard size of tatami mats is actually slightly different from one part of Japan to another, but for this Project we decided on a unified standard size so as to make them easier to use in the gymnasiums where the evacuees gather. Sometimes the evacuees themselves have to move the tatami, so we also made them as lightweight and soft as possible. We consulted among ourselves and worked out improved versions.

We knew from the outset that if the Project did not begin with inspecting the state of the evacuation centers where disaster victims were gathered, sending in supplies only simply out of our desire to lend a hand could end up being more trouble than help. This is why we consider it important that our local tatami shop members be the recipients of the mats. They are the members of the community that is in trouble and they deliver the mats as needed, because what is needed and when is something that only those in the disaster zone can know. This is a project that we can continue thanks to the presence of thoughtful tatami shop owners all over the country.

【Interview:January 2019】

Compilation: TJF

©The Japan Forum