Fascinated with Ghosts

vol.1

Ghost Stories for Tourism

Koizumi Bon, Shimane Prefecture

2015.10

©Nakasai Chiya

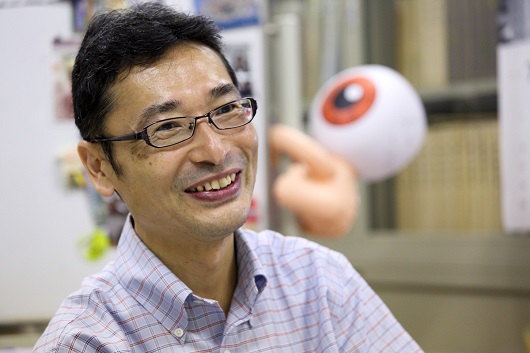

Koizumi Yakumo (Lafcadio Hearn; 1850-1904) was a writer and journalist who wrote down in English and introduced to the world many ghost stories and folk tales of old Japan. His great grandson, folklorist Koizumi Bon, is now finding ways to reawaken interest in the ghost stories and the spirit behind them that is the legacy of his well-known ancestor.

Encounter with Koizumi Yakumo, the Folklorist

When I went to university I decided to major in folklore studies, but I didn't connect the subject to my great grandfather. He was a writer and man of literature who retold old Japanese tales. I somehow assumed that was a whole different field from folklore studies. I hadn't even read his books.

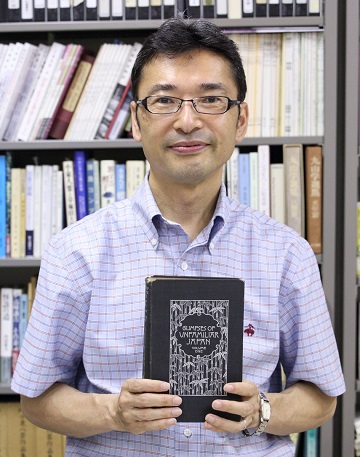

While I was working on my master's degree, when I needed to read some essays in English, a friend sent me a copy of an essay that had been published in the Journal of American Folklore entitled "Lafcadio Hearn, American Folklorist." I had to find out what was in this article about my great grandfather, and when I got out my dictionary and began to read, it was eye-opening. At a time when the word folklore studies did not yet exist, he was writing and researching as a pioneer in the field.

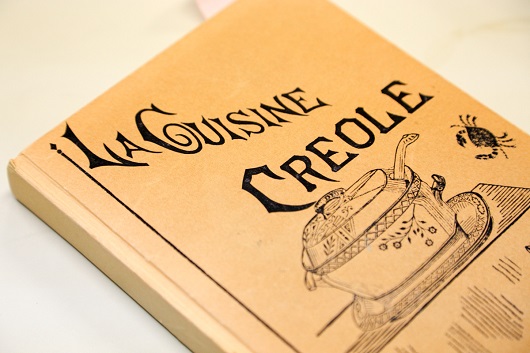

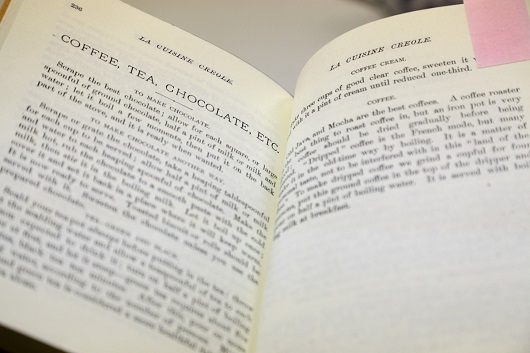

As described in the article, Hearn was born in Greece and brought up in Ireland, and before he came to Japan he had been working in New Orleans as a journalist. While in New Orleans, he wrote articles about Creole culture (mixture of French, Spanish, and African cultures). He helped edit a dictionary of Creole proverbs and he even collected Creole recipes. In other words, he had been a folklorist just like me!

It makes perfect sense, of course: ghost stories (kaidan) and folk tales are one aspect of folklore studies. It was embarrassing that I had missed the connection.

©Nakasai Chiya

Lafcadio Hearn's recipe book for Creole cuisine.

©Nakasai Chiya

The Truth in Ghost Stories

©Nakasai Chiya

Yakumo--the name I use for him--wrote many books about ghost stories including his famous Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (1903) and Shadowings (1900). He used to say that there was always some truth in the kaidan, and it seems to me that he sought insight into human nature through the ghost stories. I did not really understand what he meant by that until 2011 when I visited the Ishinomaki in Miyagi prefecture one month after it was devastated by the earthquake and tsunami that year. I went to see the members of the local Michinoku Yakumo Kai, a group of Yakumo enthusiasts, who had been evacuated in the wake of the disaster.

The rubble still exuded the stench of ruin and death as they showed me around, and one person remarked, "Right near where you are standing, only recently searchers found a woman, her child held tightly in her embrace." Such pitiful stories reminded me of the story familiar to everyone in Yakumo's hometown of Matsue. As retold by Yagumo, it goes:

There is an ameya, or little shop in which midzu-ame is sold,--the amber-tinted syrup, made of malt, which is given to children when milk cannot be obtained for them. Every night at a late hour there came to that shop a very pale woman, all in white, to buy one rin worth of midzu-ame. The ame-seller wondered that she was so thin and pale, and often questioned her kindly; but she answered nothing. At last one night he followed her, out of curiosity. She went to the cemetery; and he became afraid and returned.

The next night the woman came again, but bought no midzu-ame, and only beckoned to the man to go with her. He followed her, with friends, into the cemetery. She walked to a certain tomb, and there disappeared; and they heard, under the ground, the crying of a child. Opening the tomb, they saw within it the corpse of the woman who nightly visited the ameya, with a living infant, laughing to see the lantern light, and beside the infant a little cup of midzu-ame. For the mother who had been prematurely buried; the child was born in the tomb, and the ghost of the mother had thus provided for it,--love being stronger than death.

https://archive.org/details/glimpsesunfamil09heargoog, pp. 165-66.

Standing amid the rubble in Ishinomaki, I thought I really understood why it was that Yakumo had so deeply treasured the kaidan stories.

The Open Mind versus Human-Centered Thinking

©Nakasai Chiya

Yakumo also emphasized that human beings had to live in harmony with nature. This message can be seen in his some thirteen works about insects. The subject of insects doesn't come up very much in literary writings by Westerners, but he seems to have felt at home in Japan where people are so fond of the sounds of insects.

In early 1894, shortly before Japan plunged into a war with China determined to prove its strength through victory, Yakumo gave a lecture at Kumamoto High School, entitled "The Future of the Far East," in which he applauded the simplicity of life in Japan, saying "The fittest to survive are those best able to live with her [nature], and to be content with a little."

While living in Kobe, Yakumo became interested in the relationship between natural disasters and the Japanese, and wrote a newspaper article on earthquakes and national character, expressing his belief that the environment of Japan in which the earthquakes, typhoons, and floods were such a common occurrence had shaped people's deep-rooted acceptance of change.

So Yakumo, who loved Japan so much that he became a naturalized citizen and took the name Koizumi Yakumo, embraced the spirit of coexistence with nature that prevailed among Japanese. He described it as the "healthiest and happiest attitude toward Nature."

Yakumo detested people's tendency to think that the world revolves around them, writing that human beings are just one part of the world that is made up not only of humans but nature and the supernatural as well. Throughout his life he kept an open mind as an inquisitive student attuned to nature, the supernatural, and the human world.

We find something quite similar in the worlds depicted by Miyazaki Hayao. Miyazaki's anime portray the supernatural world and human beings are depicted from outside of themselves. My favorite of his films is Pom Poko (Heisei tanuki gassen Ponpoko), which is told from the viewpoint of the tanuki (raccoon dogs) that were the original inhabitants of the landscape in the story.

http://www.trussel.com/hearn/future.htm

Ghost Stories as Intangible Treasures of Community Culture

©Nakasai Chiya

©Nakasai Chiya

Yakumo loved Matsue, today a major city in Shimane prefecture. I myself was born and reared in Tokyo, but when I was in university, I began to travel frequently to the nearby city of Izumo, which was cooperating with my fieldwork. On these trips I would stop by Matsue, and gradually I established links with people and shopowners who had known my ancestors and relatives, and in 1987 I moved and took up residence in Matsue.

While teaching folklore studies at Shimane Prefectural Junior College I have become involved in activities to pass on Koizumi Yakumo's memory and achievements as cultural resources for own times. Famous folklorist Yanagita Kunio once wrote that "Folklore studies is not the study of things of the past; what is important is to utilize them for the benefit of the present."

Putting that idea into practice, what I have been doing since 2008 with the NPO Matsue Tourism Kenkyukai has been running the "Lafcadio Hearn's Matsue Ghost Tours," taking participants around locations that appear in the stories Yakumo wrote down in his works.

The idea for this came to me when I visited Dublin, the capital of Ireland, where Yakumo lived as a child, and participated in the "Dublin Ghost Tour." Ireland has many ghost stories and fairy tales, and I was struck at how consciously they are utilized as intangible cultural treasures in entertaining tourists. "We have ghost stories in Matsue, too," I realized. Matsue was originally a castle town, and there were plenty of stories, such as the legend of the building of the castle. But no one ever thought that such stories could be a resource for the town.

Folklorists sometimes did write down the tales, but utilizing them for tourism helps to pass them down over the generations and out into the world via the tourists.

We also work hard at training local guides for the ghost tours. We hope that such training for people of these areas will increase their interest and pride in their communities.

Sharing Yakumo's Awareness of the Senses with Children

©Nakasai Chiya

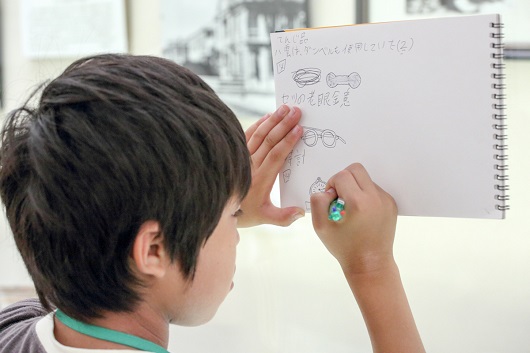

©A member of the Matsue Children's Camp avidly sketches personal items that belonged to Koizumi Yakumo at the Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum

In 2004, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Koizumi Yakumo's death, I launched "Super Herun-san Juku," children's summer school, as a joint project with the city of Matsue. Held once a year for 3-4 days during the summer school vacation period, the camp is an educational program aimed at nurturing awareness of the five senses for children from fourth through ninth grade. In 2015 it was held for the 12th time.

The camp began with the idea of passing on to children who will lead Matsue in the future the legacy of Koizumi Yakumo--who is also known to the children as Herun-san, Lafcadio Hearn. The part of that legacy that we wanted most to share was his attention to nature and humanity through all five senses. In the early 2000s, there was much discussion of the lack of opportunities for children to come into contact with nature. Surveys showed that only 40 percent of children had seen a sunrise or a sunset firsthand. It was a time when almost every child had a game console or device and children's use of mobile phones, too, was rapidly spreading; that was the era when children's "virtual" experiences were vastly outweighing their actual contact with their social and natural environment.

Yakumo lost sight in his left eye at the age of 16. Apparently his vision in his right eye, too, was poor--worse than 0.05. So it seems that he could not see things very well at all. When we read his writings with that in mind, we can detect how sensitive he was to sounds, smells, and tactile sensations. We can observe this in his book Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan (1894), which describes the sounds of insects and wooden clogs, the smell associated with a jinrikisha, and the feel of the wind on the skin.

Past Matsue Kodomo Juku programs have included events like learning to distinguish the sounds of different insects and the "blind walk" in which we walk through the forest with our eyes closed. Some of the children remarked at how they detected the smell of the forest after they closed their eyes. For the 2015 camp we devised the "Matsue Kodomo Hearn Hakkei" (Eight Lafcadio Hearn Landscapes: A Matsue Children's Tour). But the tour is not just about landscapes visible to the eye; one of the eight is a "sound landscape" when the sounds of temple bells resound through the evening.

©Nakasai Chiya

Listening to Koizumi Bon's explanation at the old Koizumi Yakumo House.

It is difficult to put numerical measures to the educational effect of the Kodomo Juku. I can definitely tell, however, that the children's capacity to think not just about human beings but about nature and to learn to consider the standpoint of others has been enhanced through their participation. The experience has sparked their curiosity and imagination. Helping them to awaken their five senses has apparently nurtured their capacity to appreciate the invisible and the intangible. And because the "five-senses experience" is local, the program has encouraged children to take an interest in their local community.

©Nakasai Chiya

At Shiroyama Inari Shrine, telling children the story of the stone foxes that Yakumo loved so much.

Discovering Culture and Creativity through the Five Senses

We need to nurture children who are sensitive with all their five senses and thereby able to discover the cultural resources of their local region and make the most of them for the future. Oral literature in the form of ghost stories and folk tales are intangible cultural resources to be found not only in Matsue but all over Japan. I hope that what we have begun in Matsue will start to catch on in other parts of the country.

When I first moved to Matsue, I felt some burden because of being Lafcadio Hearn's great grandson and did not want others to think things came easily to me because of my family connections. But since I've become involved in the Ghost Tours and the Kodomo Juku, such pressures don't even come into play. People may still harbor such assumptions, but I think I have moved beyond that and now all that concerns me is my urge to make the most of Yakumo as a cultural resource for the Matsue area and for the world.

People seem to find it easy to remember my name: Koizumi Bon, and I'm happy to be called just "Bon-san" by people I meet around the town.

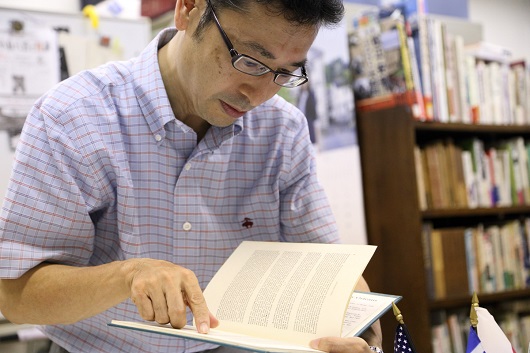

©Nakasai Chiya

First edition copy of Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan by Lafcadio Hearn.

©Nakasai Chiya

Interview by Yamagishi Hayase (freelance writer), August 2015